A marchand-mercier’s invention

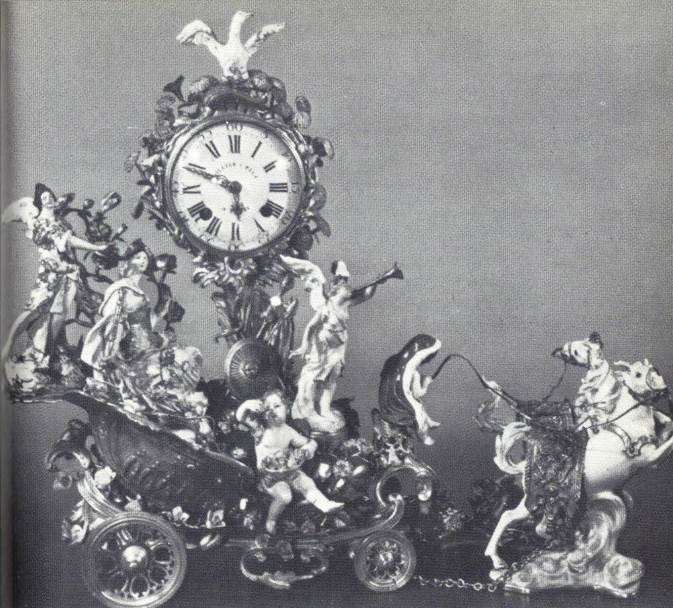

A Louis XV gilt bronze and porcelain clock in the form of Mercury’s chariot,

the watch movement signed De Lamotte à Paris – circa 1750

The Meissen porcelain figures 18th Century

The French soft-paste porcelain flowers 18th Century

Height: 27 cm. (10 ½ in.) Width: 40 cm. (15 ¾ in.) Depth: 11.5 cm. (4 ½ in.)

The chariot sits on revolving wheels which can be drawn forward by pulling the horses.

Provenance

Collection of Paul Guillaume Ledoux; his sale, Paris, 24 April 1775, lot 102

Chayette & Calmels, Drouot, Paris, 8 April 1991, lot 209 (ill.)

Literature

L’Art et les Enchères en France, Drouot, 1991, p. 259 (ill.)

Pierre Kjellberg, Encyclopédie de la pendule française du Moyen Age au XXe siècle, Paris, 1997, p. 147, B (ill.)

Comparative literature

W.Einsingbach and F.X. Portenlänger, Calden, Schloss und Garten Wilhelmsthal: amtlicher Führer, Bad Homburg vor der Höhe, 1980, pp. 52-54 and p. 53, fig. 37.

La fabrique du luxe: les marchands merciers parisiens au XVIIIe siècle, exh. cat., Paris, musée Cognacq-Jay, 29 September 2018 – 27 January 2019, pp. 37-48, pp. 142-147

Stéphane Castelluccio, ‘Le commerce des porcelaines de Saxe et de Chantilly au XVIIIe siècle’, in M. Deldicque (ed.), La Fabrique de l’extravagance. Porcelaines de Meissen et de Chantilly, Éditions Monelle Hayot, 2020, pp. 214-227.

Paul Guillaume Ledoux

Painter, member of the Académie de Saint-Luc and a dealer in paintings in Paris, Paul Guillaume Ledoux lived in rue Saint-Martin, in the parish of Saint-Josse. His name features amongst the buyers at the dispersal of large collections from the mid-18th Century, such as that of the Duc de Tallard in 1756. At the start of the same year, Ledoux was the subject of a complaint concerning a problematic commercial transaction involving a Flemish painting by David Teniers the Younger purchased from another Parisian merchant in the rue Saint-Honoré.

Clearly proud of his success, Ledoux published an advertisement in La feuille nécessaire on 9 April 1759 inviting “connoisseurs” to come and admire at his home two major paintings “of a very great price”. One, by Guido Reni, depicted Cleopatra and the other was a Madonna by Murillo. These paintings are probably those mentioned in the collections of Marie-Joseph, Duc de Tallard (1684-1755) and Jérôme Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain (1674-1747).

In the spring of 1775, Ledoux decided to give up his dealing activities in order to “be able to enjoy the rest his long labours have deserved”. He offered his collection at an auction organized by the expert François-Charles Joullain. The sale began on 24 April 1775 in the Maison de Saint-Louis, rue Saint-Antoine, where “paintings, bronzes, marbles, porcelains, lacquers, engraved & other precious stones, furniture & curiosities” were offered.

This clock in gilt bronze and Meissen porcelain is minutely described under lot 102:

« Une petite pendule sur un char à quatre chevaux conduit par un enfant. On y voit Mercure tenant une bourse, & un petit Coureur derriere le char qui est entouré de fleurs : il est de cuivre doré d’or moulu, ainsi que les harnois des chevaux ; toutes les figures & les fleurs sont de porcelaine de Saxe. Cette pendule est un petit chef-d’œuvre : elle est sous une cage de verre, & sur un pied de bois doré. »

(A small clock on a four-horse chariot driven by a child. We see Mercury holding a purse, & a little runner behind the chariot which is surrounded by flowers: it is of copper gilded with ground gold, as are the harnesses of the horses; all the figures & flowers are of Saxon porcelain. This clock is a small masterpiece: it is under a glass cage, and on a giltwood base.)

The sale’s expert did not give the clockmaker’s name because it doesn’t appear on the dial, only on the movement. The dimensions stated in the catalogue “12 pouces [32.48 cm]” high, by “16 pouces 6 lignes [44.66 cm]” wide are those of the “glass cage” intended to protect this beautiful and rare clock.

The porcelain figures on the clock are most likely the work of Johann Joachim Kaendler (1706-1775), the creative genius for the figural production of the Meissen factory. Naturally painted French soft-paste flowers enrich this elegantly chased and gilded bronze composition conceived by a Parisian marchand-mercier.

Two other Parisian clocks with Meissen figures modelled by Kaendler are stylistically very close to this example. A larger, more elaborate version from the collections of Baron Alexander Ludwigovich Stieglitz (1814-1884) is now in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

Louis XV gilt bronze and Meissen porcelain clock in the form of a triumphal chariot – mid-18th Century

Height: 52 cm. Width: 55 cm.

St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museums, Winter Palace (inv. ЗФ-23674)

The second similar chariot clock is in the Landgrave’s bedroom at Schloss Wilhelmsthal in Calden near Kassel and is illustrated in Einsingbach and Portenlänger, op. cit., fig. 37. The complex was built between 1743 and 1761 and is one of the most important rococo palaces north of the Main. The chariot of the Landgrave’s clock transports Minerva preceded by Fame and crowned from behind by Peace, all accompanied by putti symbolising the seasons.

Louis XV gilt bronze and Meissen porcelain clock in the form of a triumphal chariot – circa 1760

Dimensions unknown. Calden, Schloss Wilhelmsthal

The role of the marchands-merciers in the creation of Meissen porcelain clocks

The refined sophistication of 18th century French interior decoration comes about through the close collaboration between the marchands-merciers and a veritable network of Parisian artisans with unparalleled savoir-faire.

Under Louis XV in Paris, the powerful corporation of marchands-merciers constantly invented new luxurious objects for a wealthy clientele eager for unique pieces and innovative taste. These rare clocks adorned with Meissen porcelain are magnificent testimonies to the boundless imagination of these French merchants. Truly designers in the modern sense, they had the idea of combining clock-making with gilt bronze and Meissen porcelain which was particularly popular with great amateurs in the early part of the reign of Louis XV.

The fashion for porcelain flowers soon prompted the marchands-merciers to incorporate them as well in all sorts of forms: not only clocks but fountains, candelabras and candlesticks, potpourris, bird cages, chandeliers, lanterns and inkstands. Rapidly, a few reputable merchants specialised in these items adorned with delicate porcelain flowers initially from Meissen itself or soon after from the recently established factory at Vincennes then Sèvres.

One of them, Michel-Joseph Lair (1732-1759), recorded at rue du Roule under the sign of Le Roy des Indes, was a “privileged merchant and ceramicist (faïencier) to the King”. Many items of Meissen porcelain remained in his stock at the time of his death, including several clocks fitted, as here, with watch movements, foliage and Meissen porcelain figures. He was the proud owner of the imposing clock now in the Petit Palais in Paris, then described as: “a masterpiece of a large clock garnished with an organ, mounted in gilded copper and ornamented with Meissen porcelain flowers and sixteen Meissen porcelain figures” and priced at the large sum of 2,000 livres

Organ clock with a monkey concert in Meissen porcelain and gilt bronze, movement by Jean Moisy – circa 1755

Height: 130 cm. Width: 85 cm.

Paris, Petit Palais (inv. ODUIT 1790

Edme Choudard-Desforges was another faïencier in the Meissen porcelain trade also located in the rue du Roule. The inventory of his store, drawn up in December 1759, lists a quantity of porcelains from Saxony (as Meissen was known in the 18th century), some of which are richly mounted, as well as a few clocks supported by various porcelain subjects. Based in the rue Saint-Honoré, Jacques-François Machart (active 1744-1763) enjoyed a prestigious clientele and presented in his shop elegant objects of art in Meissen porcelain magnificently mounted in gilt bronze. Machart employed the best Parisian workshops of bronziers and gilders. When he went bankrupt in 1763, several clocks are recorded featuring Meissen porcelain subjects, but none with a Mercury chariot.

Finally, there is Lazare Duvaux (ca. 1703-1758) – undoubtedly the most famous Parisian marchand-mercier – who was based in rue Saint-Honoré under the sign of the Chagrin de Turquie. Duvaux counted among his clients Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour, all the high aristocracy and the circle of powerful financiers. His business was prosperous and the purchases of his many customers are known from the famous “livre-journal du marchand bijoutier ordinaire du Roy“, which still survives.

Several more or less elaborate clocks adorned with Meissen porcelain are cited in this stock book between 1748 and 1758: one was invoiced for 900 livres on 16 October 1749 to the banker Camuset: “A clock on a Meissen dog, furnished with plants and flowers from Vincennes on the terrace and ornaments in gilt bronze”; one sold to Mme de Pompadour on 11 June 1751, with a “group of Meissen porcelain, mounted on a gilt bronze terrace and branches, the flowers of Vincennes, the movement simple” at 490 livres. On 21 January 1754, the Chevalier Lambert bought “a clock on a gilt bronze terrace and other ornaments, on a Meissen group, with varnished brass branches imitating nature, adorned with very beautiful Vincennes flowers” for 830 livres. On 16 December 1755, Mme de Pompadour received “a clock with Meissen figures, very ornate, mounted in bronze with flowers” for the large sum of 1,800 livres.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to match most of these descriptions with the examples that survive today, making it impossible to identify the marchand-mercier who created these fascinating orders. Thus, the clocks decorated with Meissen porcelain still reveal only a tiny part of their mysterious history.